He Did the Job. He Followed the Law. He Was Fired Anyway.

For Clyde Martin, serving as a poll worker was never about money, recognition, or politics. It was about duty.

A retired resident of Limestone County, Mr. Martin volunteered at the polls after a friend encouraged him to help. Over time, he became one of the most experienced election workers at his precinct. Eventually serving as poll inspector, the official responsible for ensuring elections are conducted lawfully and fairly.

That responsibility, Martin says, is exactly what cost him his position.

A Longtime Resident, A Willing Volunteer

Mr. Clyde Martin is originally from Jackson County but has lived in Limestone County for nearly three decades. After retiring, he volunteered to work elections, serving approximately four years as a poll worker and two years as a poll inspector.

“I certainly wasn’t doing it for the pay,” Martin said. “I volunteered because it mattered.”

Before the events that would end his service, Martin says he had no personal relationship with Nehemiah Wahl, whom he knew only as “John Wahl,” and had encountered solely in an official capacity at the polls. His only other interaction with the Wahl family was helping a relative install a small solar system, long before any dispute arose.

Warnings at the Polls

From his earliest days as a poll worker, Martin says he was warned by fellow workers about recurring issues involving the Wahl family.

“They would show up at the last minute and want poll workers to sign affidavits stating they knew them and allow them to vote without proper ID,” Martin recalled. “Under pressure, two of the workers would sign. I would not.”

According to Mr. Martin, this pattern repeated across multiple election cycles.

When COVID disrupted normal staffing, Martin stepped into the role of poll inspector after the regular inspector declined to work due to a family health crisis. With that role came increased responsibility and scrutiny.

The ID That Changed Everything

During a subsequent election, Mr. Martin says “John” Wahl presented an ID that appeared official, complete with a state seal and photograph. Wahl explained it was a press credential issued by the State Auditor’s office.

Mr. Martin accepted the ID at the time but immediately sought clarification.

Alabama law requires a state-issued photo ID for in-person voting. Press credentials are not listed as valid identification.

Mr. Martin contacted Judge Charles Woodroof, the county’s chief election official, seeking guidance. According to Martin, Woodroof declined to get involved.

“I asked him multiple times to come to the poll or provide direction,” Martin said. “He wanted nothing to do with it.”

Before the next election cycle, Mr. Martin messaged Wahl directly from the ALGOP website, informing him that the media badge would no longer be accepted and that he would need to vote provisionally or present a valid state-issued ID.

From Enforcement to Accusation

That decision, Martin says, triggered his removal.

According to Mr. Martin, Wahl complained to Judge Woodroof, alleging that Martin was using his position to create a hostile environment. Wahl alleged he was violating his Constitutional right to vote. The irony, he was NEVER not allowed to vote. Mr. Martin gave him an option of voting a provisional ballot or present a valid state ID, and this was a preemptive planning, not the day of the election. Martin was summoned to a quorum to include the Probate Judge, the County Clerk, and the Sherriff, and left believing the matter had been resolved.

The next day, he received an email informing him he had been fired as a poll worker.

“I’ve never been fired from a job in my life,” Martin said. “I was angry at first, then frustrated. I did what the law required and I was punished for it.”

The Cost of Doing the Right Thing

The experience left a lasting impact.

Professionally, Mr. Martin lost a role he took pride in. Personally, he says the situation challenged his faith in the system he volunteered to uphold.

“I take pride in doing the right thing, even when it costs me,” he said. “People in my community know they can call on me if they need help. That hasn’t changed.”

What did change was his trust in election oversight.

Seeking Vindication, Not Attention

After his removal, Martin tried to share his story through official and public channels. He filed complaints with the Alabama Attorney General, the Secretary of State, national party officials, and media outlets.

He was interviewed by local television and radio, though not always sympathetically. He credits journalist Kyle Whitmire with accurately documenting his experience.

“I wasn’t trying to be political,” Clyde Martin said. “I was trying to clear my name.”

Years later, after Wes Allen was elected Secretary of State, Mr. Martin re-filed his complaint. Allen did contact him and explained that the matter would not move forward because the local district attorney declined to pursue it.

That decision raised additional questions for Mr. Martin.

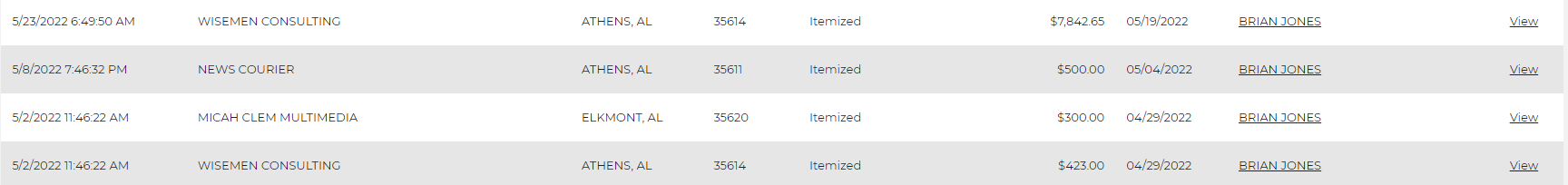

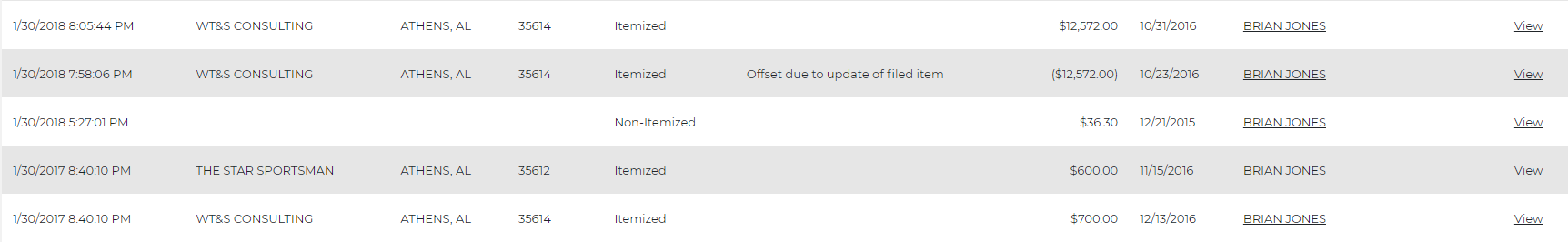

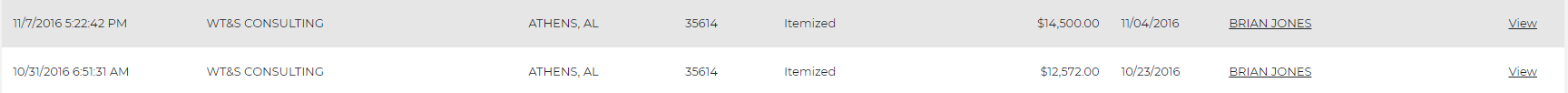

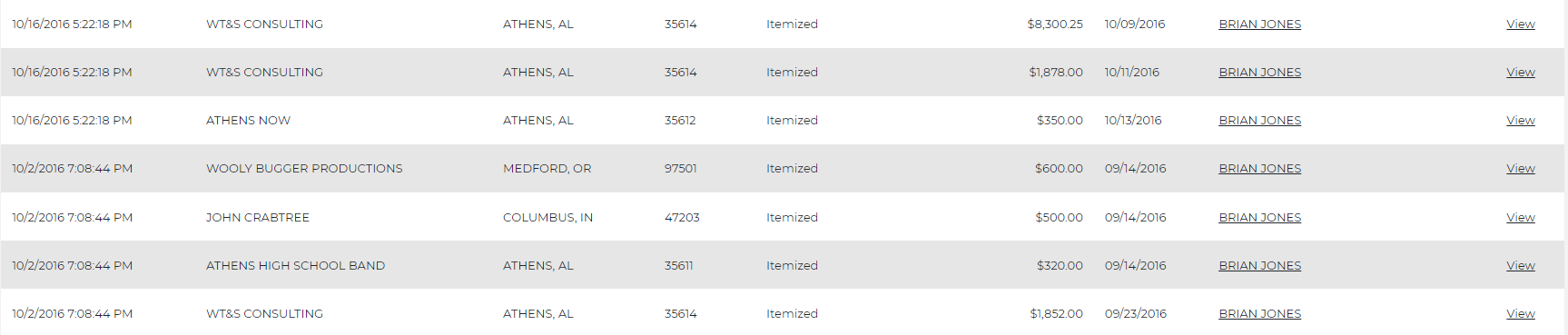

Public records and local party involvement show that Brian Jones, the Limestone County District Attorney, has been involved with the Limestone County Republican Executive Committee, a body long associated with the Wahl family. Records also indicate that Jones previously used the Wahl family’s political consulting firm during earlier campaign cycles. Campaign finance records reflect that several local Republican officials, including District Attorney Brian Jones, have utilized the Wahl family’s consulting business, which operates under multiple names such as Wiseman Consulting and WT&S Consulting.

Collectively, payments to these entities total more than $60,000. As discussed in earlier reporting, such financial and political ties naturally raise questions about whether meaningful action can be expected when allegations involve long standing allies.

Mr. Martin has questioned whether those overlapping political relationships may have influenced the decision not to pursue the complaint.

From our own experience covering local governance and transparency issues, we have encountered similar barriers. Despite multiple phone calls and emails to the district attorney’s office seeking clarification on unrelated matters, we have not received a response. We have also been made aware, through third parties, of statements attributed to Jones discouraging others from engaging with us, statements that mirror claims previously raised against other individuals who asked questions or sought transparency within the local party structure.

We cannot independently verify the motivations behind those statements. However, the pattern raises broader concerns about how dissent, oversight, and internal accountability are handled when citizens, or party members, ask uncomfortable but lawful questions.

At the center of Martin’s case remains a simple issue: a poll inspector followed election law, sought guidance from the appropriate authorities, and was removed anyway. Whether political relationships played a role is a question the public deserves to be able to examine openly without retaliation, silence, or character attacks

Community Support—and Lingering Questions

Despite the outcome, Martin says the support from his fellow poll workers and community was overwhelming. One poll worker quit immediately in protest. Another resigned after the election cycle. Neighbors across Elk Estates, Cairo, and Lentzville continue to bring up the incident years later.

Mr. Martin also alleges that members of the Wahl family later contacted one of his neighbors to encourage her to work the polls so she would sign affidavits. She refused.

On Media Coverage and Mischaracterization

After his removal, Mr. Martin sought any avenue available to have his experience documented, not to advance a political agenda, but to seek vindication for following the law. In a small community, finding independent coverage of local election issues can be difficult, particularly when those issues involve well connected political figures.

One of the journalists who covered Martin’s story was Kyle Whitmire of AL.com, a writer widely known for holding liberal political views. That fact was later used by some critics to dismiss the reporting as partisan or to characterize Mr. Martin’s actions as part of a smear campaign or an effort driven by liberal media.

That framing misses the point.

For individuals who believe they were punished for doing the right thing, vindication often matters more than ideology. When local or traditional channels fail or decline to engage, people turn to any outlet willing to document the facts. Seeking coverage is not evidence of partisanship. It is often a last resort.

The recurring pattern, according to Mr. Martin and others who have raised concerns locally, is to deflect from the substance of the issue by attacking the messenger, labeling questions as political, dismissing critics as biased, or accusing them of bad motives rather than addressing the underlying facts.

The core issue has never been about politics.

The issue is this. Clyde Martin was removed as a poll inspector for enforcing voter ID law and for notifying a voter in advance that future elections would require a valid Alabama issued state ID. He did not deny anyone the right to vote. He offered lawful options, voting provisionally or presenting valid identification, as required by statute.

Years later, public records have confirmed that the individual at the center of the dispute was not even using his legal name at the time. In that respect, Mr. Martin’s insistence on strict compliance with identification rules was not only reasonable.

It was correct.

Mr. Martin wanted to be a poll inspector for one reason, to protect voter integrity. That is precisely what he did. And it is precisely why he was fired.

A Broader Problem?

When asked whether his experience reflects a larger issue in Limestone County elections, Mr. Martin does not hesitate.

“Yes,” he said. “The shenanigans in the local Republican Party seem to center around one family controlling who can run on the ticket. If you want to run Republican, you have to kiss the ring.”

Mr. Martin says he is not seeking punishment or publicity, only vindication.

“I did my job. I followed the law. That should never be something a poll worker is punished for.”

Editor’s Note

This article is based on a recorded interview and firsthand statements from Clyde Martin. It is published for informational purposes using public records, direct testimony, and previously reported media coverage. The Limestone Lowdown will continue examining election administration, accountability, and transparency in Limestone County.